Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

The value of talk in the job shop and how culture builds sustainability

Lean manufacturing efforts should also consider the human side of efficiency metrics

- By Tim Heston

- February 20, 2023

- Article

- Shop Management

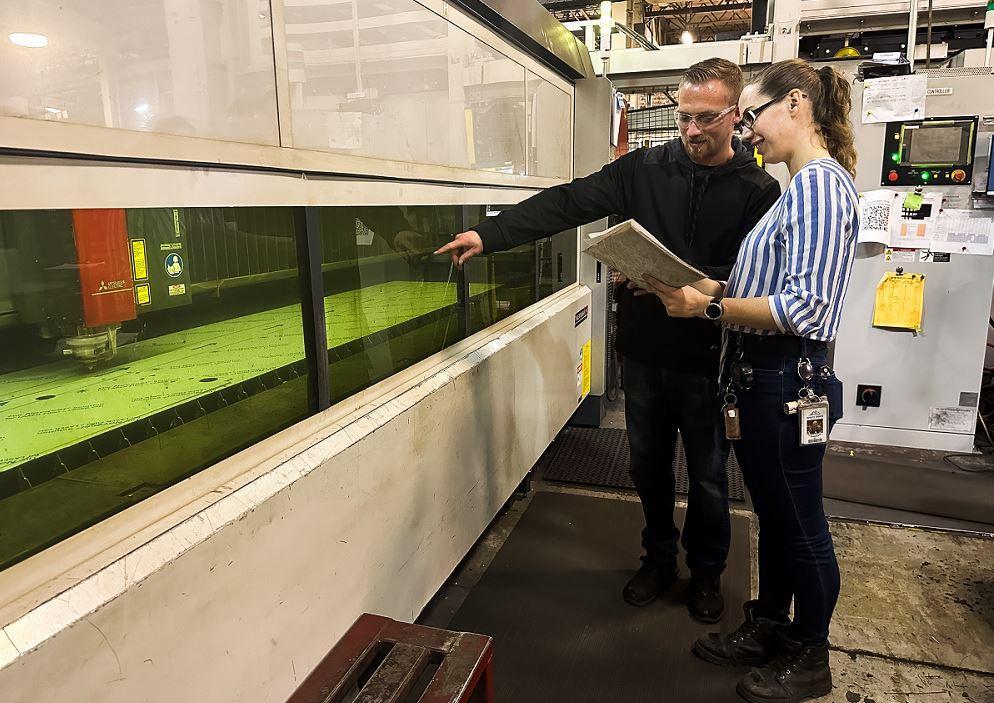

Production team members from Colorado-based shop White Rock Manufacturing Solutions collaborate on a laser cutting job.

Unexcused absences and employee turnover: If both continue to rise, month after month, year after year, a fab shop probably has a shaky future. Most first point to external factors. Fabricators compete fiercely for talent, so of course turnover is on the rise. What if current employees just don’t show up? Finger-pointing to external factors again ensues. The labor market’s tight. People just don’t want to work anymore.

And so, the churn continues. Turnover stays high, people unexpectedly don’t show up, everyone scrambles to catch up, the workplace becomes chaos, those with management authority fret and firefight, those remaining on the front lines look on with amusement as they think about their next place of employment.

Some of the most progressive shops I’ve visited share some common traits. They reinvest in the business, with new or upgraded machines, facilities, and software. They also update their metrics and keep them on display for all to see. Seeing months-old rework or equipment utilization data isn’t very useful. Most critically, they never focus on one metric in isolation. A punch might have fantastic utilization by the end of a shift, but none of that matters if a part revision was missed and the machine spent hours punching the wrong parts.

Metrics require context, a human context. An ever-increasing machine uptime metric might seem great, but what does it really mean for the people involved—that is, employees producing parts and the customers buying them?

Customers don’t care how much machines run, just as long as they get quality parts on time. What about employees? Here, the people at White Rock Manufacturing Solutions, a Colorado-based fabricator, have some insight. Recently, they reconsidered their use of water spiders—that is, the material handlers who deliver material and stage tooling for operators. Conventional wisdom says that this arrangement keeps machines running and a shop producing. White Rock, however, uncovered some hidden costs: the lack of ideas, especially those small improvements that wouldn’t come up at a formal kaizen event.

Like most fabricators, White Rock produces hundreds of different jobs, and each could have one or more “micro” improvements that might come up during casual conversation. The team found that by having operators deliver parts downstream, their conversations spurred improvements that until recently had been entirely overlooked. From a purely numbers perspective, tiny efficiency gains might or might not make a significant difference, at least not immediately. But the shop culture implications could be significant.

Sure, machine uptime might suffer a tad, but if the ideas from these meetings increase the velocity of work through the shop, lower machine utilization is probably worth it. And yes, maybe employees spent a few minutes chatting about the Broncos game. But was that time really wasted? Maybe not, especially when looking at the metrics from a human perspective.

No doubt, dedicated material handlers add tremendous value, and it still doesn’t make sense for trained operators to spend half their day walking to and from faraway workstations. But if they never move, they end up rarely talking with co-workers. Such isolation might spur apathy as they finish one part after another after another. They feel like a cog in a well-worn wheel. They clock in, clock out, go home, and maybe dream about another kind of life. Engagement falls, turnover and unexcused absences rise, and problems mount. Getting rid of water spiders entirely probably isn’t the solution, but keeping operators always tied to their machines isn’t the answer either.

Fabricators measure a range of metrics, including a few that show how much value their workers are producing: sales per employee, margin per employee, even value-adding productivity per payroll dollar. The last takes total sales, subtracts inventory costs, and divides that by the total payroll expense (excluding benefits). The result answers a simple question: For every dollar you pay people, how much does the business get in return? Past FMA surveys have shown that fabricators on average get more than $2 for every $1 they pay employees. The result strips out inventory costs, which can muddy other metrics.

Even so, there’s no one tell-all metric. The mix of work—contract versus one-off orders, volume, order consistency—can alter the overall sales numbers and achievable margins, so employee efficiency can seem like it’s falling when it’s really not. Moreover, what’s happening if employee efficiency is through the roof, yet so is turnover and unexcused absences? If a shop’s front line is in perpetual churn, how sustainable is a fabricator’s success?

Part of the solution might be to, again, get people talking. Our former columnist Jeff Sipes called this “everyday kaizen.” It might do more than unleash efficiency; it might help build a shop where good people want to stay.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI