Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Mergers and acquisitions in fabrication: Making better together a reality

The strategy behind White Rock Manufacturing Solutions’ growth from Colorado to Arkansas

- By Tim Heston

- February 11, 2023

- Article

- Shop Management

The small shop remains the backbone of precision metal fabrication, built on close customer relationships and word-of-mouth reputation. But what about scaling up as opportunities arise, especially as OEMs reshape their supply chains with near-shoring and reshoring in mind? Also, what about the industry’s graying ownership? When boomers retire and the kids aren’t interested in taking over, what then?

Demand and demographics are driving investors from private equity and elsewhere to take another look at the fragmented custom and contract metal fabrication business, hence the uptick in acquisitions the industry has seen in recent years.

Clay Reiser is part of that trend. He entered custom and contract metal fabrication in 2003, and he’s no stranger to the world of company acquisitions. The companies he’s worked for have been acquired and have done the acquiring. And in 2018, he moved to Colorado to become president of White Rock Manufacturing Solutions, a private-equity-backed organization set to go on the acquisition path.

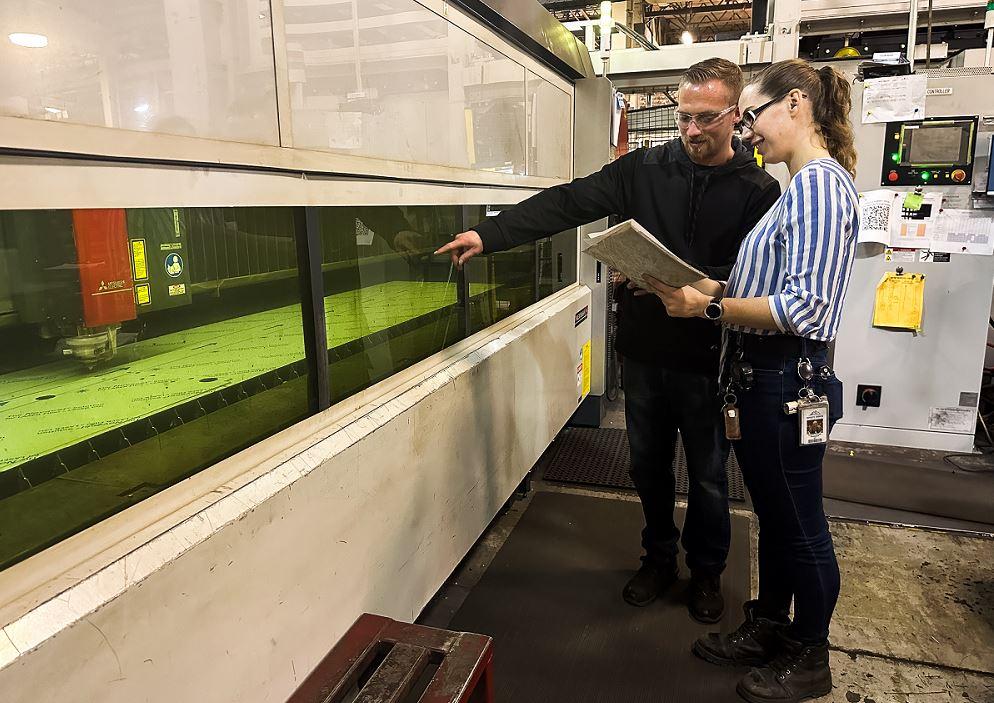

In 2018, White Rock made its first purchase when it acquired Precision Metal Manufacturing (PMM), a precision sheet metal fabricator near Denver. PMM launched out of a garage in 1998 with just two customers and grew to become a $10 million enterprise—the quintessential metal fabrication success story. Also in 2018, White Rock purchased nearby custom coater Pro Tech Powder Coating.

In 2020, it acquired Fab Tech Inc., a precision fabricator in Van Buren, Ark. In 2021, it acquired Capital Bending, a precision tube bending operation in Austin, Texas; and in 2022, it acquired Mustang, Okla.-based IG Inc., which specializes in stamping gaskets (rubber, metal, and other materials) as well as other hard tooling processes.

Metal fabrication is a small-company business, and that’s where White Rock has focused its acquisition efforts. The five companies acquired over the past five years might seem disparate, but they have a common thread of customer service and have complementary manufacturing processes. It’s one organization offering a multitude of services that, in turn, should help foster closer partnerships with customers.

Now at 175 employees, White Rock has a strategy that isn’t unique. Plenty of fabricators scale with more services and locations—the one-stop-shop approach. What sets it apart is the organization’s subtle approach to unifying disparate brands under one umbrella.

“You can use more than one mousetrap to solve a problem,” Reiser said, adding that overbearing, top-down management can keep those mousetraps forever hidden. Uncovering and improving upon those mousetraps is what makes a collection of small companies truly better together.

The Sales Strategy

A fabricator with capacity, combined with a proven record of on-time delivery of quality products, can grow extraordinarily quickly—but sometimes that growth comes with a lot of risk. A shop might invest in more cutting or bending capacity and complement it all with automation that helps boost throughput. Key customers send the company more and more work. Pretty soon, the shop is so busy serving existing customers, dollars from new customers take an ever-shrinking slice of the revenue pie. Prospecting efforts wane, quoting turnaround time slows, and revenue concentration goes through the roof.

“Our goal is to have quotes turned around within 24 hours,” said Justin Hill, account manager at White Rock. He added, though, that quick quoting just scratches the surface. “We’re now really focusing on the customer experience.”

Reiser chimed in. “What does that mean and how do we do it? To start, we need to establish a vision. We’ve got the people, and we’re starting to establish job descriptions, processes, roles, so we can change our sales organization.”

This involves shifting to a platformwide sales strategy: Salespeople now sell White Rock’s complete portfolio. That said, Reiser and Hill tread carefully here. Cross-selling without adequate attention to detail opens the door to miscommunication or, even worse, overselling and underdelivering. Shifting from, say, just selling tube bending to selling jobs involving bending, cutting, forming, and machining involves a lot of planning and coordination. Here’s where White Rock’s operational strategy comes into play.

A Philosophy on Management

“I’ve done the acquiring and have been acquired,” Reiser said. “I’ve been on both sides of the food chain.”

He’s also familiar with how multiplant operations can become competitive. Corporate planning meetings tend to focus on plant-level performance. If something’s awry, top managers charge specific plant managers to work with their local leadership teams to turn things around.

Reiser added that he isn’t one to judge. Such operations can be extraordinarily successful. To differentiate, though, he wanted to take another approach—one that started with an insight that often doesn’t make its way up to the C-suite: “Let’s be honest, most people don’t like being managed.”

He clarified that by “being managed,” he referred to top-down management styles—environments where people change because, well, they’re told to change. Some might like the new way, others might not and, hence, seek greener pastures. This means the company hires not just to grow but also to replace the talent that just left. “And we don’t want that. That churn of employees forces us to compete for the same workers everyone else needs.”

When ideas for change don’t come from “on high” but from within the ranks, the situation changes. Change occurs almost naturally as everyone works together to make their work lives better.

That sounds great, but how does White Rock make this happen, exactly? First, the company has implemented a reporting system that supports collaboration among plants.

Managers from different plants meet to discuss plant-specific metrics and share best practices. One key metric is the cost of poor quality (COPQ), which captures rework rates along with several other factors. “They then send the White Rock corporate team a single report,” Reiser said. “The COPQ and other measurements are White Rock metrics, not a metric for individual plants. I don’t want meetings to devolve into a finger-pointing session. ‘This plant’s doing great. This plant isn’t. And don’t even get me started about that operation.’ How does this help anyone?”

Because metrics are “White Rock-wide,” plant-specific operational and quality managers have a vested interest in talking about issues, helping others improve, and collaborating to get better. Competing with other White Rock plants gets them nowhere.

“For instance, when quality managers from different plants communicate, they start asking questions,” Reiser said. “‘I have this plating or painting issue. How are you guys conquering this?’ Someone else says, ‘We solved that same problem recently by installing a plug near the flange.’ Tiny bits of information are shared among the quality team, and over time our [White Rock-wide] COPQ metric goes down. That’s how we improve.”

From these meetings come ideas that help shape companywide best practices. As just one example, Reiser described a recent idea that actually called into question the long-held belief about who should move material and when.

A common tool in the lean manufacturing toolbox is the water spider, someone who stages tools and materials for machine operators. On the surface, the concept makes perfect sense. After all, any time an operator leaves the workstation to move material, the machine isn’t producing. If machines aren’t producing, the operation isn’t as efficient as it could be, right?

Not necessarily. Why? It has to do with a lack of communication. When plant managers don’t communicate, they don’t share best practices, and inefficiencies stubbornly remain—and as it turns out, the same is true on the shop floor. Sure, operators shouldn’t spend half their day retrieving tools from a far-off toolroom, but what about communicating with operators at downstream processes?

Reiser described one instance in which a press brake operator transported parts to the hardware insertion department. Sure, they spent a few minutes talking about the Broncos game, but they then began talking about the parts at hand. These two parts had a material issue. They don’t meet requirements, so I’ve marked them with a red X. I haven’t scrapped them yet, though, so you can use these to set up your machine.

They’re in the middle of the operation, the issue is top of mind, and the parts they’re talking about are physically right in front of them—a job that would have already come and gone by the next day’s morning huddle. Moreover, such conversations can dovetail to broader topics like part presentation and orientations, specific challenges in forming and hardware, even suggestions for job routing changes.

Sure, machine uptime might decline a bit, but customers don’t pay for machine uptime. They pay for quality products delivered in the right quantity at the right time. Running machines don’t make money; they cost money. Shipped jobs make money. If machine uptime is high, but so is COPQ, the operation effectively spends more to ship less. As White Rock has found, those ideas from employee interactions have helped reduce COPQ and improve throughput—benefits that more than outweigh the slight decrease in machine utilization.

Complementing these informal meetings between operators on the floor are formal meetings that promote continuous improvement—and here, a little competition among co-workers isn’t a bad thing. As Hill explained, “Once a month, our operators and leads participate in events where we challenge them to come up with ideas for process improvement. It could be relocating materials or tooling, reorganizing a work area, or anything else. They’ll submit the ideas, and we’ll take the top three suggestions and implement those processes, then reward those individuals who come up with creative ideas.”

How Long Does a Job Really Take?

A lot of inefficiency in metal fabrication occurs not from machinery problems but from communication issues, and much of that stems from events that occur in quoting and engineering. People in the office throw a job “over the wall” to manufacturing, who then pull their hair out trying to solve a problem that should have been addressed much sooner. An overlooked problem in engineering can snowball into a shop-floor avalanche.

According to Hill, White Rock avoids this first by establishing manufacturability reviews before answering a request for quote (RFQ), then by performing a thrice weekly engineering review for all new work in the order-processing queue.

“Of course, we want to catch all the issues we can before we win a project,” Hill said, “but if we don’t, these engineering reviews, which take an hour or two, allow engineers to sit down together, go through all the parts on their lists, and review them again for manufacturability.

“Also, these engineering operations are treated the same way as those at workstations on the floor,” Hill continued, explaining that those reviews are incorporated into the overall order-to-ship measurements. Jobs sitting forever as work-in-process on the floor might reveal a bottleneck. Similarly, jobs that require extensive engineering reviews can also reveal a bottleneck operation in the office. Treating engineering as a workstation helps White Rock analyze how long a job truly takes.

About Partnerships

Transactional business, where it wouldn’t take much for customers to pull up stakes and leave, can be risky—hence the drive toward partnerships. Promoting communication across the organization, from the front lines upward, help White Rock retain its internal customers (its employees) as well.

“We’re aiming for that partnership mentality,” Reiser said. “I want to provide a good service at a fair price. But at the end of the day, for our organization to make money, we need to give career opportunities for our team members and help them prosper. Otherwise, we get into that cycle of hiring against every other company that’s looking for people—and we don’t want to do that.”

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

AI, machine learning, and the future of metal fabrication

Employee ownership: The best way to ensure engagement

Steel industry reacts to Nucor’s new weekly published HRC price

How to set a press brake backgauge manually

Capturing, recording equipment inspection data for FMEA

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI